Delusions can affect people with dementia — causing individuals to believe loved ones have been swapped for impostors. Here’s help for managing such symptoms.

7:00 AM

Author |

If you have a loved one with dementia, and they constantly ask if you are "really you," they may have Capgras syndrome.

SEE ALSO: 5 Strategies to Help Caregivers Practice Self Care

Capgras syndrome, also known as Capgras delusion, is the irrational belief that a familiar person or place has been replaced with an exact duplicate. Daughter Mary becomes a pretender while "Real Mary" is somewhere else.

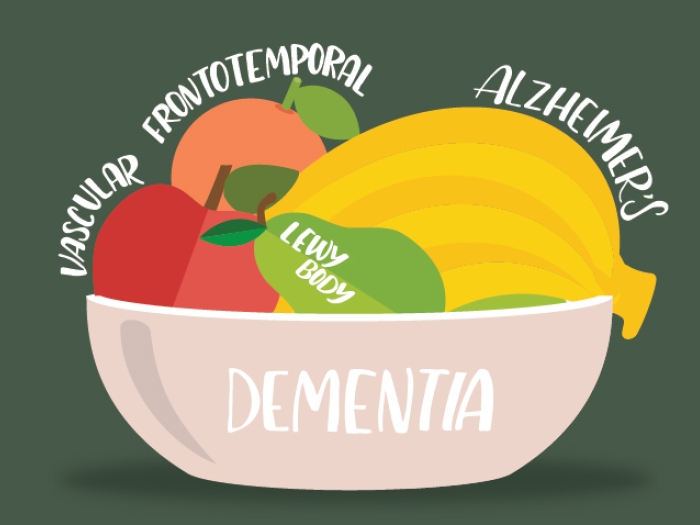

Capgras, named for Jean Marie Joseph Capgras, the French psychiatrist who first identified it, is commonly seen in people with neurodegenerative illnesses like Alzheimer's disease and related dementia.

One study published in the journal Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders looked at the prevalence of misidentification syndromes (Capgras is in this category) in 650 patients with a variety of neurogenerative diseases. The study found that Capgras-like events occurred in about 16 percent of the Alzheimer's and 16 percent of the Lewy body dementia individuals in the study. It isn't commonly seen in frontotemporal dementia.

In dementia patients, the Capgras delusion can come and go. Usually, the person or people who are around the most become the impostor. When and why the person with dementia believes this isn't understood.

This delusion is sometimes also seen in individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, or those with brain injury or disease.

Coping with Capgras syndrome

Capgras is particularly painful for the family to witness. Usually, the closest caregivers are the ones accused of being an impostor. These individuals are also vulnerable to exhaustion, isolation, and doubts about how they are handling things.

It's important to remember that Capgras is a symptom of the dementia, not your loved one's true belief. Because it is a delusion (a fixed false belief that can't be reasoned with), no amount of reassurance, argument, or proof changes their mind.

What you can do first

With any of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, such as Capgras, we always try behavioral and environmental interventions before medications. The following can help family members manage:

- Don't argue with the belief. That just makes the person angrier and more convinced they are right.

- Go with the emotion. Acknowledge your loved one's fear, frustration, and anger.

- Change the focus or redirect your loved one. Try to distract them with an activity, music, or a car ride.

- Agree to disagree about this belief. Remind them that no matter who you are, you love and care for them and are there for them.

- Be creative. In some cases, the caregiver accused of being an impostor may be able to leave the room to get the "real" person, then come back in and no longer be perceived as an impostor.

When your loved one needs medical intervention

If the Capgras delusion causes great distress to the person with dementia, or the person is putting themselves or their caregivers in danger (hitting at them), a medical evaluation (and possibly medication) is warranted.

SEE ALSO: Alzheimer's: Not Just a Disease for Older Adults

During the medical evaluation, make sure the physician checks for the possibility of a bladder infection, and that any pain, constipation, and heartburn (which are hard for a person with dementia to communicate) are treated.

Memory medications such as rivastigmine (Exelon), galantamine (Razadyne) or donepezil (Aricept) can reduce these psychotic symptoms in certain dementias.

Occasionally, a medication that reduces delusions (an atypical antipsychotic) could be used, but not as the first-line approach unless this is causing significant distress for the patient.

The takeaway

Capgras is a symptom that is as painful for the person with dementia to experience as it is for their family to see happening.

Understand that Capgras and other symptoms, such as hallucinations, other delusions, anxiety, and depression, are symptoms due to brain changes and not how the person truly feels. This can enrich the caregiving experience.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!