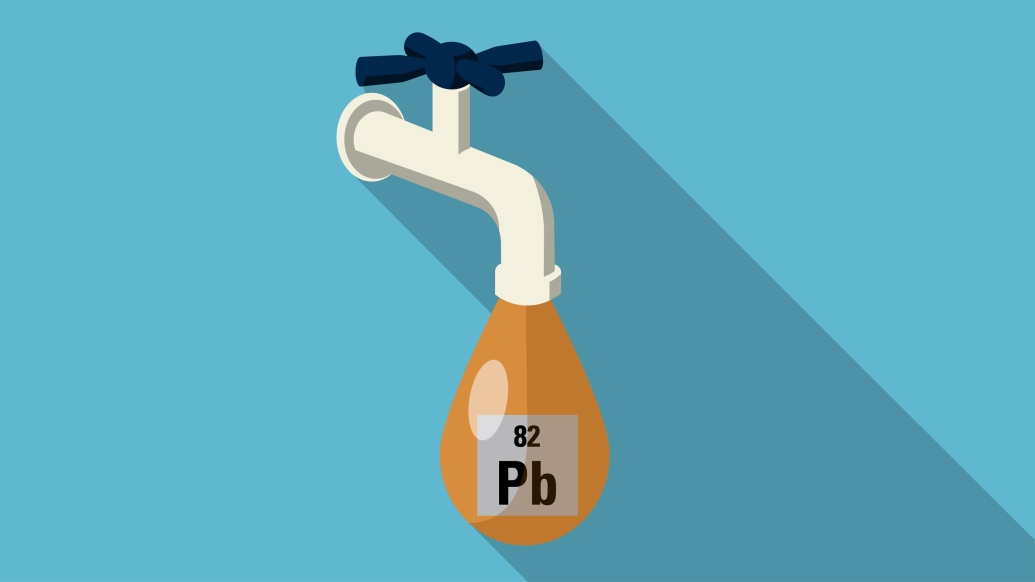

The recent Flint water crisis — and a new American Academy of Pediatrics statement — highlight the danger lead poses to children.

6:45 AM

Author |

Lead poisoning rates in children have decreased dramatically in the past 40 years. But far too many children remain exposed, according to a new position statement in Pediatrics, the journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

"There is no identified threshold or safe level of lead in blood," the authors of the statement, published June 20, wrote.

SEE ALSO: Tick Talk: How to Stop and Remove Them

The Flint water crisis served as a recent reminder of the ongoing issue, "[raising] the national consciousness of lead risks," Flint pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha, M.D., MPH, recently told a group of doctors and researchers at University of Michigan's C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

"It's not a problem of yesterday," she said.

Hanna-Attisha, who helped uncover the water quality issues in the city, spoke to the Mott Child Health Evaluation and Research Unit. She talked about the dangerous health consequences of lead seepage into the drinking water for the community's children. She explained how and why Flint was so vulnerable, and how community leaders are responding.

She also noted that the spotlight the crisis shone on lead exposure risks to children all over the state has been positive. More health officials and state leaders are paying attention to long-standing problems, especially in impoverished communities.

As the issue continues to garner attention nationwide, many parents might be concerned about lead and its effects on children. Sharon Swindell, M.D., a pediatrician and childhood lead poisoning expert at C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, explains what families need to know below.

Science tells us that this toxin could hinder learning, long-term achievement, classroom performance and cause behavior and other issues for young people. There is simply no safe level of lead, period.Sharon Swindell, M.D.

Why is lead exposure among children such a concern?

Swindell: We know lead is a neurotoxin. We know children are experiencing major brain development. Research shows that even low levels of lead have been associated with developmental issues, such as school difficulty, poor attention span, impulsivity and lower IQ scores. The Flint water crisis has prompted research specifically looking at how lead exposure during pregnancy may affect miscarriages, newborn deaths and other health issues for the fetus. Science tells us that this toxin could hinder learning, long-term achievement, classroom performance and cause behavior and other issues for young people.

There is simply no safe level of lead, period.

What is the most common source of lead exposure?

Swindell: Lead from water accounts for an estimated 10 to 20 percent of elevated lead levels in children. [But] the bigger risk for lead exposure is found in the buildings where children spend most of their time, usually their home, and sometimes a family member's home, daycare or school.

Chipping or peeling paint in old homes is the biggest culprit for childhood lead exposure. If your home was built before 1978, the paint may have lead in it. Deteriorating paint can create lead-containing dust, especially in areas around windowsills and door frames. Little ones known for picking up toys and putting them into their mouths are especially at risk of ingesting lead this way. Exterior paint in homes may also land on the soil kids play on in their yards. There have also been cases of children eating lead paint chips, which reportedly have a "sweet" taste.

Lead is also found in water, with older homes most likely to have lead pipes and fixtures. As old pipes deteriorate, this form of lead exposure may increase in many communities. Even newer "lead-free" plumbing may contain as much as 8 percent lead. Old toys and furniture may also have lead-based paint.

See this checklist from the Environmental Protection Agency on whether your home may be putting your family at risk for lead poisoning.

Who is most vulnerable to the risks of lead exposure?

Swindell: The effects of contaminated water will likely vary, depending on how each child's body absorbs and responds to the toxin. Babies whose only source of nutrition is formula made from tap water are of particular concern because of the sheer volume of water they consume relative to their little bodies. Children under the age of six and those with iron deficiency or poor nutrition are also at higher risk, as greater amounts of lead may be absorbed.

What about bathing in or cooking with lead-contaminated water?

Swindell: The risk of lots of lead absorption through intact skin is low, though greater for those with eczema or other skin conditions that may leave skin open. Our main concern over young children bathing in lead-contaminated water stems from the possibility that they may swallow water in the tub and that this may add to other sources of exposure.

As for cooking with potentially contaminated water, guidelines recommend using cold tap water that has been ideally flushed for several minutes before using. If there is possible lead contamination in the water, however, it is best not to cook with it at all. Hot tap water may increase chances of leaching.

What should you do if you're worried about lead exposure in your home?

Swindell: By law, house sellers must disclose whether their home has been tested for lead. If the answer is no, a buyer may ask for it to be tested, but they often waive that option.

If you do live in an older home and are worried about lead exposure, you may get your house tested. Make sure testing includes windowsills and door and window frames. If there is lead in the paint, find a lead-abatement certified builder to help strip and replace it. Never do this yourself or with a child in the home.

What are the symptoms of lead poisoning?

Swindell: Lead poisoning usually has no clear symptoms. Some children may have stomach pain, constipation, headaches or seem irritable. However, there are often no overt symptoms of lead poisoning. That doesn't mean there's minimal harm. Children's developing brains and nervous systems are susceptible to toxins and even small amounts of lead exposure add up over time, increasing risk of developmental effects.

If there are no obvious symptoms, how is lead poisoning identified?

Swindell: Almost all U.S. children are at risk for lead poisoning although some children are at higher risk than others. It's important for pediatricians to identify children who may have higher risk of lead exposure by asking families questions about their home environments. This is especially true in industrial cities, families remodeling older homes, low-income communities that may have older homes in poor repair, families who are changing housing more regularly and may not know the lead status of the homes, or even unresponsive landlords. If risk for exposure is identified or parents are concerned, a blood test for lead should be checked.

Childhood lead levels in Flint were studied before and after the city changed its water source, helping identify the risks. The goal is for all children to be screened for lead poisoning, however; these tests will only show elevated blood lead levels at the time of screening — not show if a child was previously exposed and still at risk of experiencing the consequences.

How do you treat lead poisoning?

Swindell: There is no good treatment for lead poisoning in kids. Research shows that removing a child's exposure to lead will help stop the progression of effects, but we don't have any medicine that reverses the harm that's occurred. A chemical process called chelation therapy helps remove heavy metals like lead from the blood, but it is reserved for very high levels of lead poisoning and is not used for the vast majority of exposed children due to the risk of side effects.

When it comes to childhood lead poisoning, prevention is key.

How have risks of lead exposure changed over time?

Swindell: We've come a long way in reducing lead exposure, but it's still a risk. Public health measures over the years have made a significant difference in minimizing the risk of lead exposure for kids. Blood lead levels have dramatically decreased over the decades because of stricter federal laws, such as preventing builders from using lead paint in building interiors and in pipes and restricting leaded gasoline. Pediatricians are also more aware of the need to identify children at risk of lead exposure and who should be tested.

Recently reported records prompted by the Flint water crisis also show problems with American drinking water infrastructure in communities with homes and commercial buildings built before the mid-1980s. Some of these communities still supply tap water through private service line connections that leach lead into the liquid.

See the most recent county-by-county breakdown of childhood lead levels in Michigan (2013) here.

How have pediatricians like yourself reacted to the Flint water crisis?

Swindell: What has happened in Flint is a devastating and disappointing scenario, and many communities will undoubtedly learn from this. I am encouraged to see that community leaders like Dr. Hanna-Attisha are responding appropriately on behalf of the children who have experienced lead poisoning. These children will need careful monitoring of development, early education support, good nutrition and guaranteed health care access to ensure they have the opportunity every child should have — to be as healthy as possible and to reach their full potential.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!