A new report found that lead is present in one-fifth of baby foods and other products for young children. A Michigan Medicine pediatrician shares advice.

7:00 AM

Author |

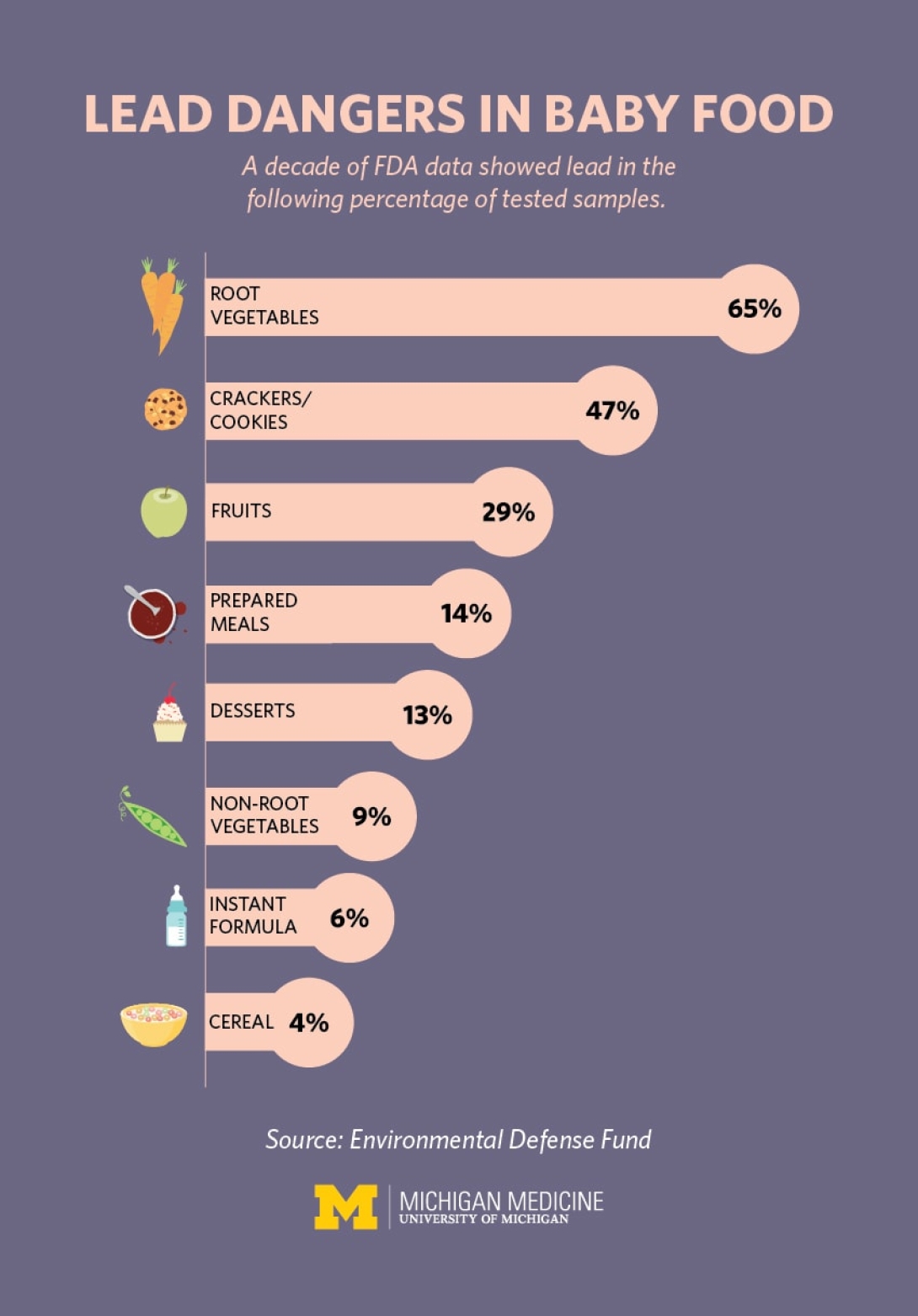

The news came as a shock to parents of infants: 20 percent of baby foods tested over a decade contained detectable amounts of lead, a recent report found.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Some types of baby food, those made of root vegetables in particular, were much more likely to contain the harmful chemical element. Of the samples with sweet potatoes, 86 percent tested positive for lead; 43 percent of carrot samples did, too.

Even worse, fruit juices marketed to babies had a much higher chance of containing lead than varieties marketed to all ages (89 percent versus 68 percent for tested grape juice and 55 percent versus 25 percent for apple juice, respectively).

The report, released in June by the Environmental Defense Fund, also found lead in 64 percent of tested arrowroot cookies and 47 percent of teething biscuits. The results encompassed 11 years of Food and Drug Administration data.

So how concerned should parents be?

"We need to take this very seriously," says Ashley DeHudy, M.D., a pediatrician at University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children's Hospital. "We often think of exposure happening through contaminated water or lead-based paint.

"This report strongly indicates that food cannot be overlooked."

Still, she says, parents shouldn't panic. The EDF report sampled foods from across the country and did not disclose brand names, which makes some conclusions tougher to draw based on a family's location and dietary habits.

But it ought to warrant increased caution and advocacy, says DeHudy.

Being a conscious consumer helps parents limit exposures their children may face.Ashley DeHudy, M.D.

Why lead is dangerous

There is no safe level of lead exposure, according to the FDA, which nonetheless maintains set levels for lead in food — benchmarks that DeHudy considers outdated and lacking current scientific knowledge.

And those guidelines vary: The FDA considers bottled water with lead content of 5 parts per billion as acceptable, for example, but fruit juice may contain up to 50 parts per billion.

SEE ALSO: How a Pediatrician Helps Her Family Eat Healthfully at Home

Children ages 6 and younger, she notes, are most vulnerable to the risks of consuming lead, no matter the amount.

"Studies have shown that higher lead exposure can lead to decreased intelligence levels — with a direct impact on IQ, behavioral problems and learning disabilities," says DeHudy.

Another big hazard: Lead, when ingested, is distributed to organs such as the liver and kidneys.

Those dangers have taken on renewed focus in light of the ongoing water crisis in Flint, Michigan, where improperly treated river water caused corrosion in lead water pipes and put thousands of young people at risk.

The presence of lead manifests in other ways, DeHudy says — namely via lingering amounts found in lead-based insecticides and emissions from gasoline that contained lead (both sources have since been banned). Remnants may be in the soil, thus affecting the food supply.

Which is why the FDA maintains that achieving a zero-tolerance standard simply isn't possible.

Based on its new findings, however, the EDF is advising that baby food manufacturers ensure that their products contain no more than 1 part per billion of lead. It also wants the FDA to update its lead limits and food safety guidelines, among other things.

What parents can do

For now, there are several ways to reduce risk (and worry) during mealtime.

Keeping the EDF report's more problematic ingredients in mind, parents should strive to feed their babies a well-rounded diet to minimize lead exposure.

"Carrots and sweet potatoes tended to be culprits, so it's a bad idea if a kid's diet consists mainly of those," says DeHudy. "Take an everything-in-moderation approach."

And while making baby food from scratch may seem like a feasible alternative, she notes that there is no way to verify that store-bought produce is lead-free. Those who make their own food should use cold water, because hot water is more likely to contain the toxin if their home has lead pipes.

Likewise, busy parents might also struggle to manage the demands of homemade recipes, says DeHudy.

She does, however, echo the advice of a recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement: Be wary of fruit juice.

The academy recommended in May that no juice be served to children ages 1 and younger and that it be offered sparingly in later years. That's in line with the EDF findings, which note that fruit juice often contains soluble lead — a form that is more easily absorbed by the body.

Says DeHudy: "Children should be eating fruit, not drinking it."

She encourages parents to talk with their pediatrician about dietary safety. DeHudy, for one, advises her clients against buying infant rice cereals because of findings that the products contain arsenic.

Such advocacy might also surface before a trip to the grocery.

"Parents can reach out to their favorite food brands: Do they regularly test for lead, and do they make those results public?" DeHudy says. "Being a conscious consumer helps limit exposures their children may face."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!