After sustaining multiple blows to the head during his college hockey career, a Wolverine returns to campus decades later for specialized neurological help.

7:00 AM

Author |

Both on and off the ice, former University of Michigan hockey player Ray Dries has a reputation for never giving up.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

During his three seasons with U-M (1982-85) Dries scored 28 goals and performed 37 assists.

Although his collegiate hockey career had many memorable moments, the most significant may be the one he remembers least: During a 1983 game against Michigan Technical University, Dries was hit hard from behind, falling headfirst into the boards.

After sitting out the next part of the game, he insisted on returning to the ice that same night.

"I felt like I was floating on the ice the rest of the game," says Dries, now 56. "I don't remember the actual hit; I saw it later, on the game film."

As was common practice at the time, Dries didn't receive prompt medical attention for his concussion, convincing his coaches that he could continue practicing and playing.

In the years since hanging up his skates, Dries found himself struggling more and more — first with memory, then with coordination and balance issues.

Looking for answers, he came to Michigan NeuroSport in 2012.

Multiple hits, many symptoms

The team at Michigan NeuroSport, a Michigan Medicine program that specializes in neurologic care for athletes, conducted a thorough evaluation to determine the origin and extent of Dries' symptoms.

SEE ALSO: The Dangers of Untreated Concussions in Kids' Sports

Neuropsychometric testing helped doctors better characterize the patient's memory issues.

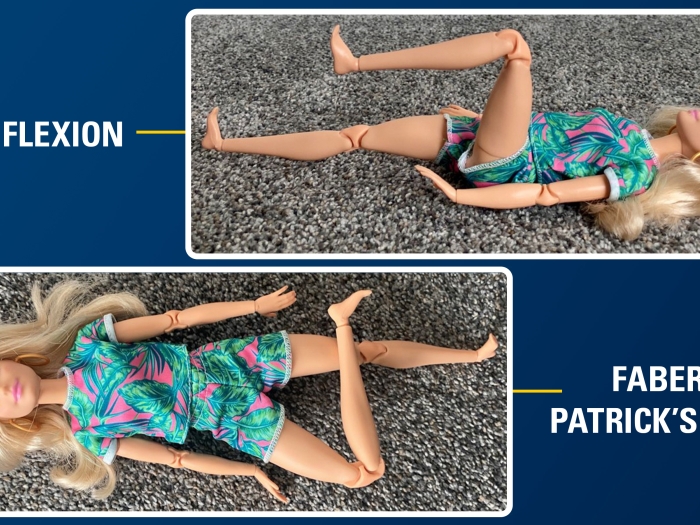

Many of his muscle-related problems fit a pattern of ataxia — a neurological condition impacting muscle control, coordination and balance — but additional testing revealed subtle signs of two rare conditions: dystonia (uncontrolled muscle contractions) and chorea (involuntary twitching).

Beyond understanding how his cluster of symptoms developed and progressed over the years, the team also considered the fact that Dries endured multiple blows to the head during his career — not just the one hit that resulted in his major 1983 concussion.

They concluded that Dries' condition met the criteria for a relatively new clinical diagnosis: traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES), a degenerative condition resulting from one or more severe blows to the head.

Clinical researchers at Michigan NeuroSport are at the forefront of proposing a framework for describing TES that can be used to arrive at a diagnosis in living patients.

Their work, published June 2016 in the journal JAMA Neurology, is a vital step toward earlier intervention and more effective treatments.

Another neurologic condition, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (or CTE), may also arise from multiple head impacts and concussion. More widely reported in the media, CTE can only be definitively diagnosed under a microscope after death.

The relationship between CTE and TES is unknown; a person who has one does not necessarily have the other.

A winning strategy

Armed with a more precise diagnosis, a specific plan was developed to manage Dries' chronic condition.

In addition to regular Michigan NeuroSport clinic visits, Dries was taught a number of practical strategies to help him compensate for memory difficulties. He also entered physical therapy, which has kept symptoms at bay.

SEE ALSO: When Concussion Symptoms Linger, a Neuropsychologist May Help

"In the three years since I started physical therapy, my problems with balance and coordination have either plateaued or are worsening at a much slower rate," says Dries, who lives in Clinton Township, Michigan.

Dries' two sons have followed in their dad's skating path, both playing hockey at an elite college level. One suffered a career-ending concussion.

Still, "we're a hockey family," says Dries. "We love seeing young people get involved in the game.

"But our experiences show how important it is to take concussion risk seriously, and get medical help quickly."

Photos by Leisa Thompson

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!