Two Michigan Medicine doctors find themselves on the other side of care after learning their baby was born deaf due to a common cold-like virus known as CMV.

5:00 AM

Author |

Odessa Scott-Craig looks up and smiles when her two older sisters, Cecilia, 5, and Fiona, 3, play. She loves music, often caught grooving and bouncing to the beat. She responds with giggles and babbling when her parents speak to her.

They're all sounds the blue-eyed, dimpled one-year-old is enjoying four months after getting cochlear implants.

Born deaf, Odessa spent most of her first 12 months of life in silence. But at 13 months old, she heard her mother's voice for the first time after her cochlear implants were activated– looking up with surprise and delight in a moment captured on video.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

"She loves 'talking' back and forth with her sisters, which is amazing to watch. Her face absolutely lights up when she sees them," says her mother Megan Pesch, M.D., who is also a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Michigan Medicine C.S. Mott Children's Hospital.

"She is now imitating vowel sounds, and has made tremendous strides in receptive language. She recognizes my voice from across the room and localizes sounds. We are so proud of her."

But it's been a long road for Odessa and her family from the time of diagnosis through surgery and ongoing therapy to ensure she gets caught up with developmental milestones she's missed because of her hearing loss.

"Odessa means 'journey,'" Pesch says. "We didn't realize when we named her how perfectly that would reflect our experience."

A silent cause

As a newborn, Odessa slept through loud alarms and barely stirred from noises made by her two older sisters. She was easily soothed with a laid back temperament.

"I thought we finally had a good sleeper," Pesch remembers.

Her newborn hearing screen at the hospital prompted a referral but false positives for such tests after birth are common enough that her parents weren't overly concerned.

When Odessa turned 10 weeks old, Pesch and husband Tom Scott-Craig, M.D., a primary care physician at Michigan Medicine's Brighton Health Center, learned the real reason noise didn't wake their baby: profound hearing loss.

"The audiologist kept checking the machine to make sure it was working and that's when I thought something might be wrong," Pesch remembers of the follow up test.

"We were shocked. We just weren't expecting that news. Our world changed."

Further tests also revealed the cause of Odessa's hearing loss: a common virus called congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV). Symptoms are often minimal, including a sore throat and swollen lymph nodes, but when a pregnant woman gets CMV, it can invade the fetus' developing brain and ears, causing irreversible damage.

One in every 150 infants in the United States are born infected with CMV, with up to 20% of them developing hearing loss and other serious symptoms.

As a pediatrician herself, Pesch had heard about CMV but didn't receive a lot of information during pregnancy. Because of her experience, she's working with her Michigan Medicine colleagues to bolster efforts to educate pregnant women about the risk, especially families with other children who may bring the virus home from daycare or school.

"When we confirmed that she had CMV I was really saddened because it's preventable," says Pesch, who recently detailed her experience in the Journal of the American Medical Association. "I'll never know exactly how I got it, but I wish I had known not to kiss my little ones on the lips or finish food off their plates – steps that may have prevented this."

"CMV is extremely common, but very few women know about it," she adds. "We've really engaged a lot of different partners at U-M to work on an initiative to increase prenatal education, awareness and screening for CMV."

Sound on

After Odessa's diagnosis, the couple had two options: Odessa could learn alternative methods of communication, such as signing, or she could get cochlear implants.

They chose the latter and at 11 months old, Odessa underwent cochlear implant surgery with a team led by Mott pediatric otolaryngologist Marc Thorne, M.D.

A cochlear implant is a small electronic device that provides access to sound by directly stimulating the hearing nerve. Young children who receive them are able to take advantage of this method of hearing to develop speech and language skills.

"By having identified Odessa's hearing loss early and intervening early, our hope and expectation is that she will perform as well or better than her peers," Thorne says. "By the time she's ready to enter kindergarten, there will likely be no obvious differences between her and any of her peers in terms of her hearing, listening and language development."

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

But Odessa will require continued therapy with a diverse U-M team, including audiologists, speech language pathologists, auditory verbal therapists and pediatric otolaryngologists through U-M's Sound Support program. Occupational therapy and physical therapy are also helping her catch up with gross and fine motor skills. She's starting to crawl and pull herself up.

She's still working on words as is expected, but is also learning some sign language, even signing "I'm done" after she's finished eating.

"Initially there was some shock and fear and then grief over realizing that she couldn't hear, and that she may have obstacles that other people wouldn't," Scott-Craig says. "But then we were able to focus on what was next, and how to get her access to language. For us, we are grateful that there have been technological advances, and for the choices today that weren't available decades ago.

"I would tell other parents experiencing this that there is a lot of hope."

A new perspective

Pesch and Scott-Craig say the experience has also given them a different perspective in their professional careers.

"As a physician you are continuing to learn not just about the science but the patient's experience," Scott-Craig says. "When something like this happens in your personal life, it inevitably gives you added empathy and perspective for what patients and families go through."

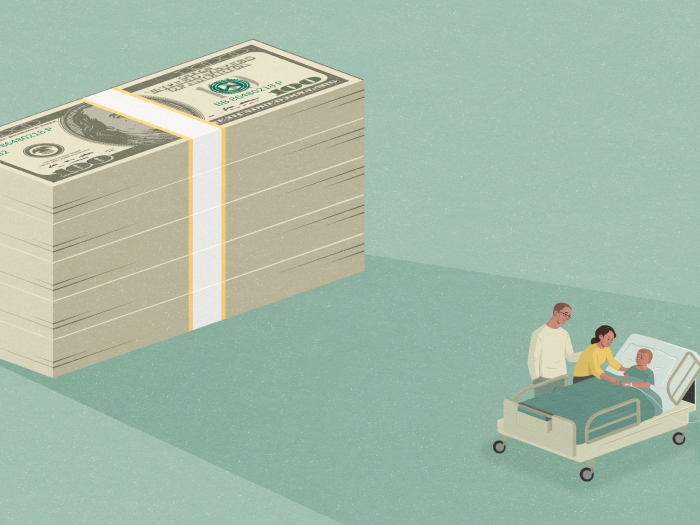

Pesch, who works with children with developmental delays and disabilities, including hearing loss, is usually the expert guiding parents on home therapies and routines to support their children's developmental challenges.

She too has deepened empathy for how much time families must invest in their children's care.

"The irony that I am now living in a world of my own advice is not lost on me," she wrote in her JAMA piece. "Life now revolves around being the parent of the patient, not the physician."

The couple is also trying to normalize their daughter's experience as much as possible, such as making sure her childcare provider has dolls with cochlear implants in the mix of toys.

And Odessa's older siblings treat their baby sister just the same, telling people that she has "special ears."

"She's going to have some additional hardware so she will always be a little different in some way but who isn't?" Pesch says. "She's making more progress every day and has brought so much joy to her family.

"She has a very full life ahead of her."

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!