The most commonly donated organ from living people has a high transplant success rate and little risk to the giver.

7:00 AM

Author |

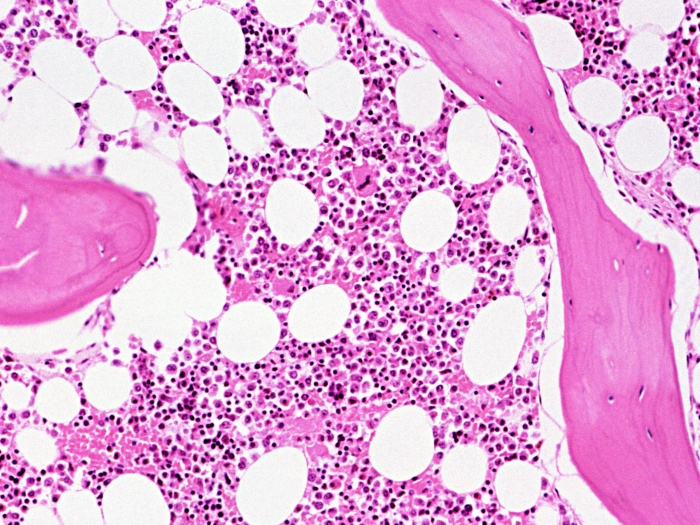

Organ and tissue donation from living people makes up about 4 of every 10 donations that take place each year. Kidneys are the most frequently donated organs from living people.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

A person may give one of their two kidneys, which provide the necessary function to remove waste from the body.

Such donors fall into two groups, says Randall S. Sung, M.D., a Michigan Medicine transplant surgeon.

"They want to help somebody they care about — a family member, a co-worker, a friend or someone in their church," Sung says. "And there also are people who want to do something good for a stranger. These are called nondirected donors."

In either circumstance, the results can be life-changing, with little risk to the donor.

That was the case for 49-year-old Michigan Medicine patient Jeff Lewis, who in December 2000 gave a kidney to his older sister, Jacqueline Lewis-Kemp. He returned to work without incident a few weeks later.

"Your life goes back to normal," says Lewis, who has written a book about his kidney donation experience. "But you will get the knowledge that you did something to save somebody's life, and that will be with you forever."

For recipients, success rates are high: About 1 percent of transplanted kidneys fail within the first month, Sung says. Two percent from living donors fail within the first year.

He spoke more about what the surgery entails:

Facts about kidney transplant

Why might someone need a new kidney?

Sung: It's always as a result of end-stage renal disease. There are several common causes, including diabetes, hypertension and polycystic kidney disease. Those patients are either on dialysis or will soon need it.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

When chronic kidney disease develops, it's often asymptomatic. It isn't until a person's kidney disease is far advanced that they can get swelling, fatigue, nausea or loss of appetite. A patient may have difficulty breathing because their body gets overloaded with fluid because the kidneys aren't getting rid of it effectively.

What are the benefits of receiving a kidney from a living donor?

Sung: There's so much of an advantage. They last longer, and they also allow the recipient to be transplanted sooner, thereby avoiding the time they would have to be on the waiting list — which can be as long as eight years.

How does a living donor prepare?

Sung: The biggest step is education and making the decision to donate. There is an evaluation process that involves testing and in-person appointments with everyone on the team. But once a donor is approved, there's really not a lot they need to do to prepare, other than stay healthy.

Any one person can usually have many compatible donors. It's usually limited only by blood-type compatibility. Sometimes, there are variables like age or size — younger donor transplants tend to last a little bit longer, for example, and a transplant for a big recipient from a small donor may not last quite as long. But we don't exclude someone from donating for those reasons.

How does the transplant operation work?

Sung: For both the donor and the recipient, the operation lasts roughly three hours. They typically come in at the same time — even though the operations are staggered. It takes much longer to remove the kidney than to prepare the recipient to implant it. The anesthesiologists put in a nerve block to assist with postoperative pain.

SEE ALSO: 7 Facts Everyone Should Know About Becoming an Organ Donor

Once the kidney is removed from the donor, it gets flushed with preservation solution and packaged in ice. Then it's brought to the recipient in the operating room where it gets put in.

Do you remove the recipient's existing kidney?

Sung: We rarely ever remove a kidney. That's a common idea people have, which is very logical. People are always surprised to hear we don't touch the recipient's kidneys. The issue is not that they are causing harm; they're just not functioning.

We put the transplant lower down in the pelvis. There are other advantages to having it in that location. Their native kidneys just sit there and don't cause any trouble. It really winds up being a lot less surgery. So these people have three kidneys, pretty much.

Could you explain any associated risks?

Sung: The complication rate is very low for donors. But in the early phases, recovery is more difficult for them. That's because of where the incision is located and also because the recipient is getting anti-rejection medications that also help with pain.

In terms of medical complexity and the complications, that's much trickier for the recipient. For any operation of this type, there are risks of wound and bladder infection and blood clots. Bleeding is more common; a blood transfusion is not out of the question. Sometimes there are issues with the ureter, which is the part we attach to the bladder.

How does kidney transplant improve a recipient's quality of life?

Sung: It can make a big improvement. One of the demonstrated advantages is not having to do dialysis anymore. Not only can dialysis be time-consuming and also tie people to where they live, but people might not feel great while doing it.

In general, people feel like they have more strength — and they usually notice it right away. It's not uncommon for a recipient to wake up from a transplant, or a day later, to say: "I feel great."

For more information or to register as an organ donor, visit the secretary of state's office online.

Visit the University of Michigan Transplant Center to learn more about transplantation.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!