The 1918-1919 flu pandemic killed millions. What can it teach us about preventing the spread of infections today?

12:48 PM

Author |

A wave of misery is washing over America right now, as the peak of flu season lays millions of people low with fevers, aches, coughs, nonstop runny noses, nausea and a general feeling of "bleah."

Even some Americans who got vaccinated against the influenza virus are feeling the effects, though far less than they would have without the vaccine.

But as miserable as this year's epidemic is, it pales by comparison with the one that swept across the country and world exactly 100 years ago.

Just ask Alex Navarro, Ph.D., a University of Michigan medical historian who has studied the historic flu pandemic of 1918-1919 for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In less than a year, the flu killed more than 650,000 Americans, and tens of millions more people around the globe.

Navarro, who works at U-M's Center for the History of Medicine, reflects on the similarities and differences between yesterday and today, and on the lessons we can learn from what our grandparents' and great-grandparents' generations endured.

He and his colleagues published an online encyclopedia of the 1918-1919 flu pandemic, including profiles of how 50 cities handled it, and how certain communities escaped the pandemic's worst effects.

Q: How was 1919 different from today – and how was it similar?

A: Of course, the major difference is that we have influenza vaccines today, which has made a major difference in preventing transmission.

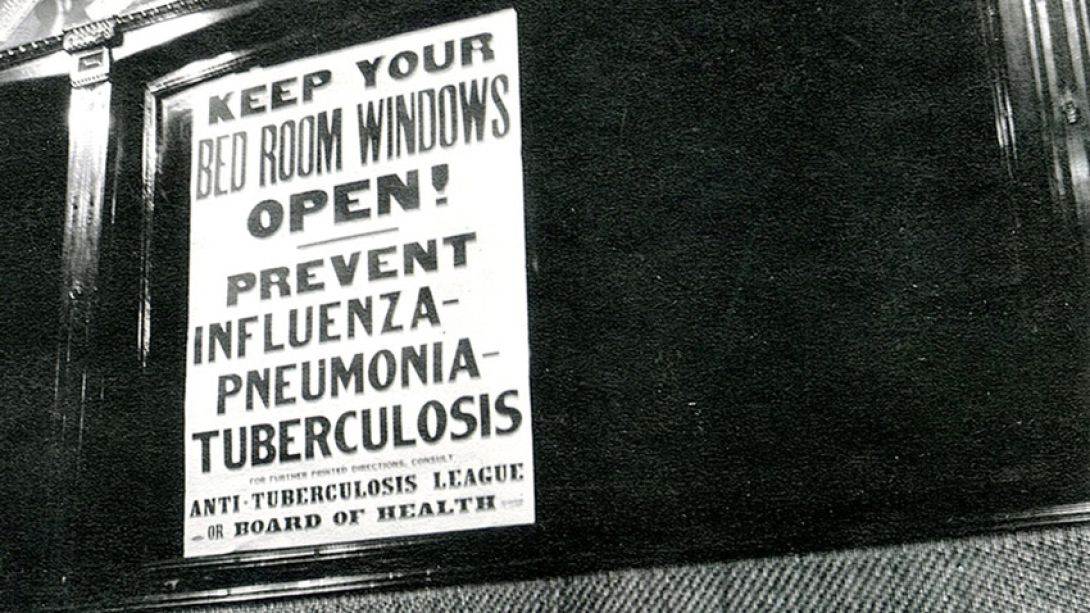

Back then, the 'germ theory' about microbes causing diseases and spreading between people was still relatively new. They still didn't know that a virus caused flu. In fact, some physicians and medical researchers thought that influenza was caused by the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae.

There were still professionals working in the public health community who were not yet full converts to germ theory, and many thought that keeping a clean heart, clean bowels, and warm feet could protect you from flu. So the science has clearly advanced since then.

But our population concentration, which has a lot to do with the spread of infectious disease, is surprisingly similar today. The 1918-1919 flu pandemic occurred right at the time when the United States was becoming an urban country. The movement of the population to cities in the late-19th and early-20th centuries was a major transformation in U.S. society. Now, 100 years later, we're back to that status. After decades of becoming more suburban in the mid-20th century, we're back to that urban concentration again.

LISTEN UP: Add the new Michigan Medicine News Break to your Alexa-enabled device, or subscribe to our daily audio updates on iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Another area where things aren't so different is communication. Of course today, we have mass media, social media and 24-hour news sources and health websites to tell us how flu is spreading and how to protect ourselves. But in 1918, a lot of people read daily newspapers, which came out at different times of day and were inexpensive. So getting the word out about prevention and the progress of the pandemic was very much possible. Our study of newspapers shows they carried many messages about the growing seriousness of the pandemic in each community and the importance of avoiding gatherings where flu could spread.

One of the major differences was in what could be done for people once they came down with influenza. Back then, medical care for influenza was rudimentary. Patients were placed in wards where they were separated by thin curtains. They didn't have the modern intensive care and breathing support technologies that we have today. But they did know that flu was a disease of congregation, and many cities either prohibited or discouraged visitors to hospitals, and encouraged many people to receive or provide care at home whenever possible.

Q: What role did immigration and World War I play in the pandemic?

A: In 1918, many of the rapidly growing cities had large immigrant communities. Health authorities had to think about how to achieve good public health outcomes in a diverse population of people living next to each other in tenements without adequate sanitation.

While sanitation is much better today, we still face similar challenges when it comes to community outreach. In 1918, public health officials had to think about how to reach immigrant communities in multiple languages, just as we do today.

In our research we found some examples of scapegoating in certain cities of certain immigrant groups, notably the Italian and Hungarian communities in Denver. When Denver experienced a second spike of influenza cases and deaths in late-1918 and early-1919, the assistant health commissioner blamed immigrants for spreading the disease by congregating at the houses of their ill family members. The case of Denver is the exception that proves the rule, however. By and large, this was the first pandemic where nationally no one group served as the scapegoat.

In some ways it was like today's opioid epidemic, hitting all sectors of society and all locations, and prompting a national public health response.

The entry of the U.S. into World War I in 1917 did play a major role. No one knows exactly how the pandemic started, but this flu hit military installations hard and quickly during a time of massive mobilization of American service members.

MORE FROM MICHIGAN: Sign up for our weekly newsletter

The war effort inspired hyper-patriotism, and a deep sense that that the nation needed citizens to do their part. While there was undoubtedly some pushback to public health orders from some residents in some communities, one gets a sense from the historical sources that compliance was widespread. In 1918, people had a greater sense of volunteerism and willingness to join the war effort as a civilian, and that extended to their response to government requests that they not congregate, or that they should wear flu masks or even volunteer to be a nurse. I don't know if we still have that in the post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era, where there is a higher level of distrust of government and officials.

We also know from historians who specialize in the history of mass media that there was more trust in the mass media, and belief in what the newspapers were reporting, than there is today. This fits with the times. It was the height of the Progressive Era, where there was a sense that experts should be believed.

Q: So why did the pandemic end? Was it because people followed the government's recommendations?

A: Our research did show a very strong association between lower influenza death rates in cities that enacted multiple public health measures such as limits on public gatherings, put them in place early, and kept them in place longer. This even applied to places like churches, and to the business community, which was called upon to close stores, and generally complied as long as they felt that closure orders were applied fairly.

These public health measures alone could not end the pandemic, however. The 1918 pandemic continued in waves into 1920 before the virus evolved into seasonal influenza. With each wave there were fewer people susceptible in the population.

Q: What can the history of the pandemic 100 years ago teach us today?

A: Of course, today we have antiviral medications, and research on vaccines that allows us to try to match the strain that is circulating elsewhere in the world before it comes to North America.

But no matter how good and quick vaccine development is, it will always be several months before a new vaccine is ready, and there won't be enough to vaccinate everyone at first, so there have to be decisions about who to vaccinate first.

In 2009 when the H1N1 "swine flu" emerged after the seasonal flu vaccine had already been developed, we saw some efforts to learn from 1918. Because children tend to be "super-spreaders" of respiratory diseases and often more vulnerable, there were widespread school closures. Generally, they were of short durations though, and not as long as they needed to be to truly be effective.

In these situations, there will always be a constant battle between how serious does the public think the crisis is, and what they are willing to comply with. This makes it very important to get information to people quickly. Social media and television news make that much easier today than in 1918. However, that information can be difficult to accurately gather and gauge early in a pandemic. In 2009, for example, the initial outbreak appeared to be much more deadly than it actually was. When people saw the crisis was not as bad as officials were warning them about, there was some pushback against measures such as school closures and vaccination efforts.

Then there is the whole anti-vaccination issue. Social media and our 24-hour news cycle can be a boon and a bane in these situations, because it makes it so much easier to spread all types of information – good and bad.

Given that schools will play an important role in halting the spread of any future pandemics, we can learn a lot from the experience of 1918. Back then, nearly every urban school had its own nurse, and most cities had very robust systems of public health monitoring of students. Today, school nurses are often shared among multiple schools.

Compared with spending in the past, the CDC and local and state public health departments have faced budget cuts, too. But we do know that the business community is engaged today like never before, including those involved in the supply chain for supplies used in outbreaks.

Explore a variety of healthcare news & stories by visiting the Health Lab home page for more articles.

Department of Communication at Michigan Medicine

Want top health & research news weekly? Sign up for Health Lab’s newsletters today!